Sänger Antipodal Bomber DECLASSIFIED

Kilroy Revealed!

by Tim Nelson

There is continuing fascination with German advanced projects from the World War II era. Most of these innovative concepts remained “paper projects,” existing only on drawing boards or in the minds of desperate engineers. A handful of designs made it to mockup or prototype stage, and a few (e.g., Messerschmitt Me-163, Me-262, Heinkel He-162, Arado Ar-234, A-4 (V-2) missile, etc.) made it into limited production. The consensus view among historians has been that most information about these projects has long been made public. However, even well into the 21st Century, new and shocking information has come to light about a project much more tangible than realized.

Background

The advanced Rakotenbomber (rocket bomber) design by Eugen Sänger and Irene Bredt had its origins in the late 1930s. They submitted a proposal to the German Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) in December 1941 for an advanced vehicle that would enable bombing of the U.S.A. The concept was to launch the machine on a long horizontal rail using a powerful expendable booster; the vehicle would continue to climb and accelerate under its own rocket power to the fringe of space and high sub-orbital velocity. In a series of encounters with the upper atmosphere, it would continue to skip and glide to its target (assumed to be New York City). Post-mission recovery in an aligned nation such as Japan was mentioned but was likely a dubious possibility. It was variously referred to as the “Amerika Bomber,” “Antipodal Bomber,” or “Silbervogel” (Silver Bird). The proposal was quickly dismissed by the RLM as impractical, although briefly (it was believed) revisited in 1944 as the tides of war turned against Germany. Recently declassified materials have entirely changed the narrative on this famous design.

We now know that in March 1945, as Soviet troops were advancing into eastern Germany, informants were able to send word to senior Allied commanders that advanced hardware was taking shape in the vast tunnel complex of the Messerschmitt facility at Walpersberg. To prevent this unknown technology from falling into Soviet hands, a special mission was launched to seize and transport the materials to the west. After the facility fell to U.S. troops on 12–13 April 1945, the hardware was quickly extracted from an area that would soon be ceded to Soviet control and become part of East Germany.

A top-secret part of Operation Lusty, the post-war Allied appropriation of advanced German technology, the strange hardware obtained at Walpersberg turned out to be special indeed – elements of three Silbervogel airframes in work. Arrangements were made to surreptitiously transport all these components across the Atlantic to an extremely remote, secret facility within the White Sands Proving Ground in New Mexico. This site was far from any significant population, more secure than Muroc Field in California, and the locals there had been made accustomed to strange happenings during the wartime Manhattan Project and postwar V-2 test launches.

Silbervogel Flight Test

Detailed examination in the Fall of 1945, in conjunction with a small number of expatriate Messerschmitt engineers brought to White Sands under Operation Paperclip, established that the hardware in hand could, with effort, support fabrication of a single complete airframe. Augmented by a select group of engineers and machinists from North American and Los Alamos, this work proceeded through 1946. Recognizing the extreme secrecy of the program, but also the advanced potential of the design, the goal was a flying prototype in early 1947.

The Sänger/Bredt technical papers were reviewed, and a critical error was found – the aerodynamic heat loads the vehicle would experience (proportional to Mach number squared) were far greater than originally anticipated. That realization, coupled with the limitations of wartime metallurgy and slave labor production in Walpersberg, led to a decision to conduct a limited envelope and light weight flight test program. The original launch rail concept was abandoned in favor of self-propelled takeoff using only the onboard engines. These engines (upsized versions of the V-2 missile ethanol/liquid oxygen engines designed by Dr. Walter Thiel) were subjected to a brief ground test program near the White Sands V-2 missile range. Speed would be restricted to low Mach numbers. Any noise complaints from the sparse population would be blamed on the ongoing V-2 test program.

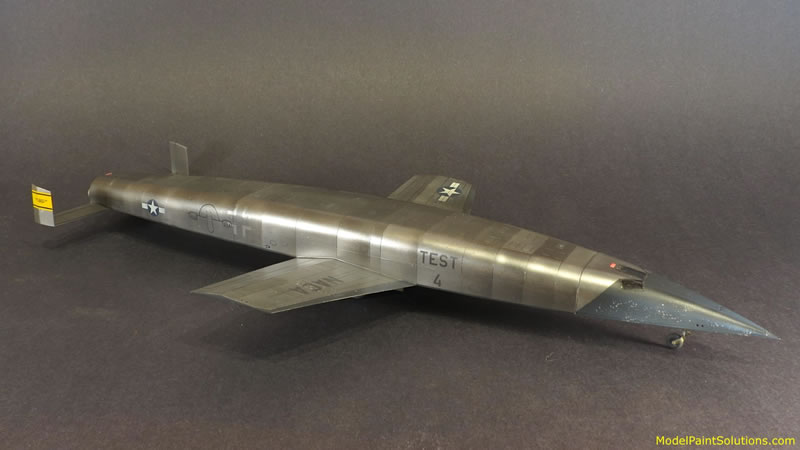

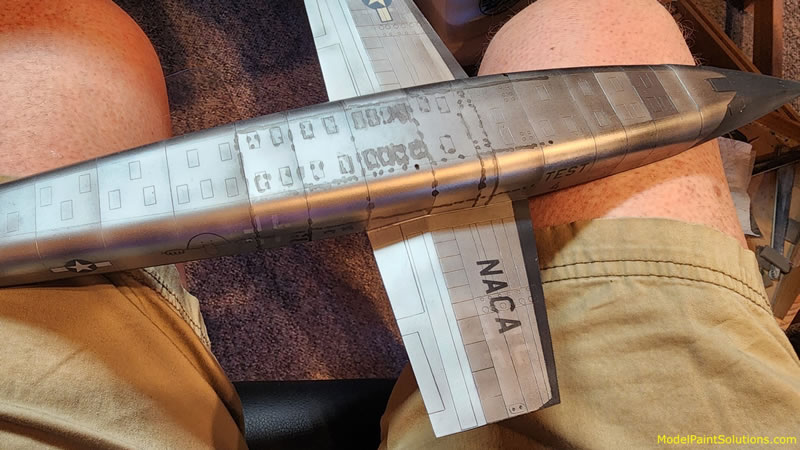

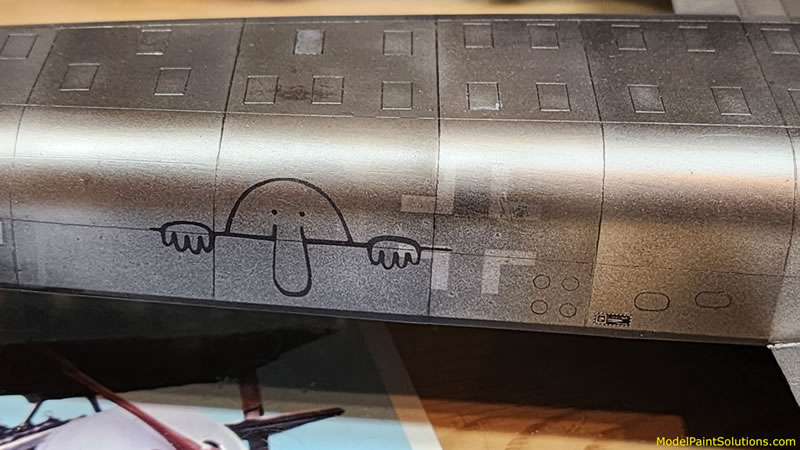

A small team of sequestered U.S. Army Air Force (USAAF), U.S. Navy (USN), and National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) personnel developed flight test plans. Airframe assembly proceeded apace. Performance data was calculated and tabulated. Ground support equipment was designed and fabricated. By Spring 1947, the Silbervogel, now christened “Kilroy” by the team, was ready to take flight. The bird had been adorned with Kilroy markings over the remaining ghost Luftwaffe insignia, as well as the first use of the future iconic yellow NACA tail band and modified standard NACA logo. The Frankenstein airframe was considered article number 4 and labelled accordingly.

The flight crew for Kilroy’s evaluation was elite. The pilot-in-command was USN Lt. Commander I.B. Fulinya, Sr., an Anacostia and Patuxent River flight test veteran (his namesake son would gain notoriety 19 years later flying the Convair XFY-1 Pogo over Viet Nam – see References). In the right seat was USAAF Maj. Johnny Doolots, a pre-war air racer and WW II veteran (also involved in the clandestine effort to ferry P-47s to Israel, and later participant in the 1949 Schneider Trophy Race – see References). Also onboard to manage systems was NACA flight engineer U.R. Fullovitt (otherwise unknown to history). The crew chief in charge of maintenance and airworthiness was seasoned Messerschmitt engineer R.U. Schittenmee (who years later would dabble as an author in obscure aviation history – see References).

Taxi tests were conducted during March 1947, building up to high speed. The vehicle was never designed for a runway takeoff, and a bad nose wheel shimmy developed at moderate speed. A damper device was quickly designed and installed to solve the problem.

On April 1, 1947, after a lengthy walk-around and preflight, Fulinya and crew lit the engines and Kilroy slowly began a long takeoff run on an unnamed dry lakebed. Thus began Kilroy’s secret, brief, and harrowing flight test program.

The first flight exceeded 60,000 ft and Mach 1, several months before Chuck Yeager’s famous X-1 flight. Control at high altitude and speed was marginal. Subsonic handling qualities were woefully deficient, characterized by general wallowing and excessive Dutch Roll. Pilot-induced oscillations in pitch were a continuing issue due to the undersized and sluggish elevator control system. (The machine would have benefited from stability augmentation but the technology was only in its infancy at the time.) Forward visibility was extremely limited. Approach speed was extreme, since the machine incorporated simple but ineffective trailing edge flaps and landing attitude was severely constrained by tail strike considerations. The only runway deceleration devices were wheel brakes, which were woefully undersized.

After an extremely challenging deadstick approach and landing back on the lakebed, Kilroy finally came to rest. The crew was sobered by the first flight experience but committed to proceed with further testing. The machine was thoroughly inspected, and repairs were made in three problem areas - hydraulic leaks, loose & damaged access panels, and complete brake replacement. By April 14, Kilroy was launched on its second flight.

Caption: The only known image – thus far - of the Silbervogel “Kilroy” at White Sands, April 1947 (photographer unknown)

It was previously determined that Mach 2.2 would be the maximum speed, taking the limitations of the airframe materials into account. In too flat of a trajectory, Flight Two overshot the maximum Mach target and exceeded Mach 3 (years before Scott Crossfield and Mel Apt) - but the airframe was irreparably weakened. The vehicle also exhibited the first signs of inertia coupling, which would plague supersonic aircraft designs for years afterward. After another hair-raising deadstick descent, approach and landing, this time flown by Doolots, a charred, battered, and smoking Kilroy rolled to a stop in the desert. Following inspection, Schittenmee and the maintenance team declared the airframe no longer airworthy and beyond practical repair.

Test reports were written and filed under special access classification, to be forgotten under the pressures of the upcoming Korean War, the pressing need for air-breathing jet aircraft, and fiscal constraints. All participants were sworn to utmost secrecy, and valuable lessons learned were locked in secrecy.

In early July 1947, Kilroy was unceremoniously scrapped at White Sands and quietly dumped in the desert near Roswell, N.M., where it could cause no further trouble.

In the Box

For decades, the only kits of the Sänger/Bredt spaceplane were limited run resin affairs such as Part Time Models or Sharkit, or paper models. That changed in 2021 with the release of a mainstream injection-molded kit by AMP of Ukraine. This author quickly snapped one up and was then shocked by the release of another (and probably better) 1/72 Silbervogel by Takom in 2022. These kits not being cheap, I lived with AMP alone.

The AMP kit is a sizeable model – 16 inches long when completed. It exhibits typical limited run issues such as flash, vague panel lines, sink marks, indifferent fit, and rough surface texture. Some kit parts such as landing gear oleo scissors were unusable due to excessive flash and replaced with scratchbuilt versions. I buffed the entire surface area with steel wool, then sanded with successively lighter grades to deal with most of the surface roughness. Since my intent was a weathered metallic finish, I didn’t sweat getting to a mirror-smooth glossy surface. I rescribed vague lines and added a couple of full-length longitudinal lines just because I thought it would look better. I added speculative reaction control thruster pairs at strategic locations – this is a spaceplane design, after all.

This model showed clear signs of being a tail sitter, so I added some ballast weight to the nose. The nose top section is clear and fit to the body is poor. Some grinding, sanding, and filling was required here.

Fit of the wings to the fuselage is vague but I figured it out, using historical drawings as a reference for something like the right dihedral. After this elbow grease phase, my least favorite aspect of modeling, the model was ready for priming. AMP thoughtfully provided cockpit window masks.

I typically use Mission MMS-001 Black Primer these days (thinned 50/50 with Mission Thinner and a dash of Liquitex Flow Aid and Tamiya Acrylic Retarder), which lays down a beautiful, robust, eggshell finish. The first round of priming really highlighted the sink marks I’d previously overlooked, so those were addressed before a second coat.

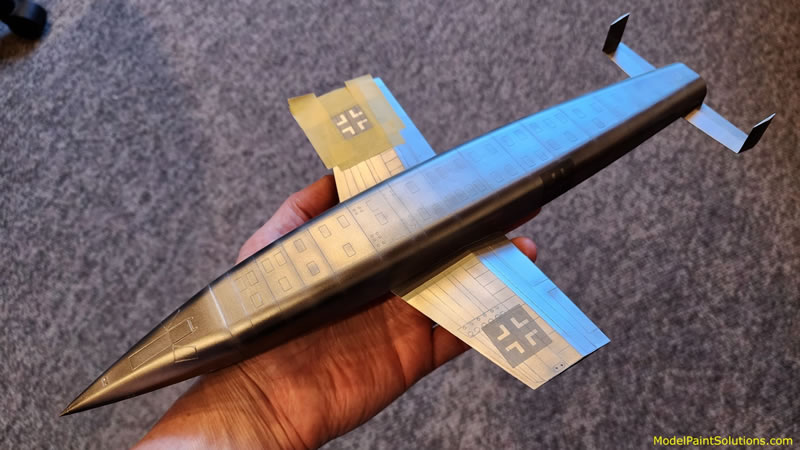

Pondering possible liveries of this mysterious bird, I seized upon the recently declassified Kilroy saga. Markings are based on apparently contemporary descriptions from the flight test crew and are an educated guess - the only known photo of the prototype is inconclusive. Time will tell if more documentation comes to light. I did some experimentation on a side test mule using Vallejo Satin or Matt as a “pre-shade” for a metallic finish – the idea being to change the reflectivity around panel lines. This mix is about 30% stock to 70% Vallejo thinner, with //no// retarder. I liked the results, so I gave Kilroy similar treatment. Next came the metallics.

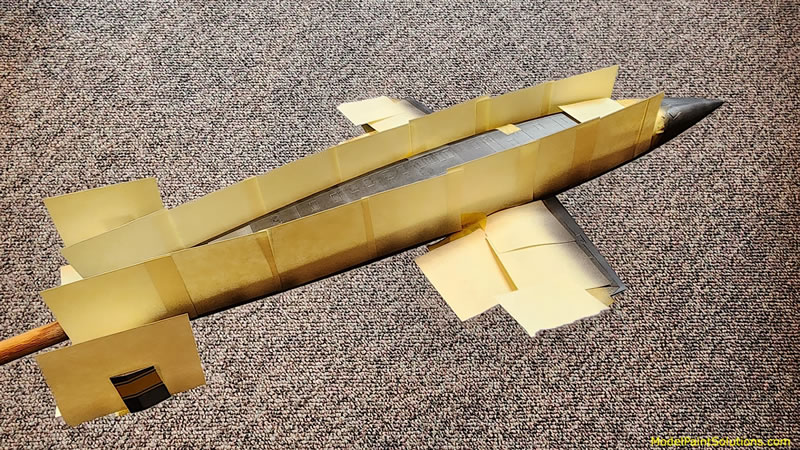

The first round of metallics was applied using AK Real Colors RC 479 Xtreme Aluminum, about 70% paint to 30% AK Nitro thinner. This was followed on selectively masked panels by AK RC 488 Matt Aluminum, thinned the same way. I made custom masks using the Silhouette Cameo for “ghost” Luftwaffe markings, which were applied at this stage as well. A few masked panels were also hit with Mission MMM-02 Cold Rolled Steel thinned about 70% paint and 30% thinner mixture (this thinner mixture itself is 30% Mission MMS-007 Clear Primer to 70% Mission Thinner, dubbed “CP30” by John Miller, with flow aid and retarder added). This completed basic airframe metallic treatment.

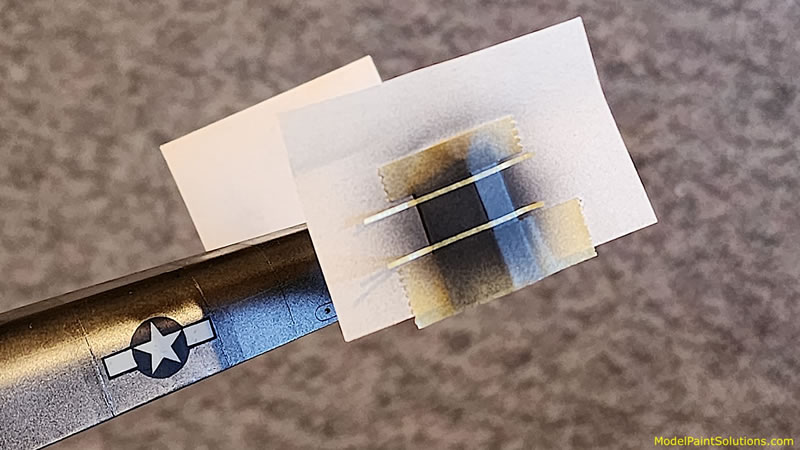

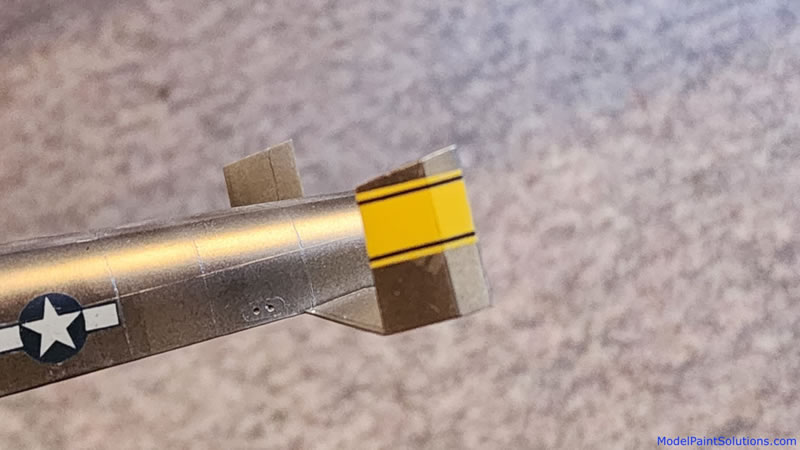

We then moved to the yellow NACA tail bands, which were painted AK RC 082 NATO Black, masked to retain stripes, then AK RC 004 Flat White, then AK RC 007 Yellow. All thinned about 50/50 with AK High Compatibility Thinner.

More masking was needed to treat the bottom edges of the fuselage, wing leading edges, and my custom Silhouette Cameo NACA and “Kilroy” markings using AK RC 082 NATO Black. U.S. “stars and bars” were also painted using masks.

Having completed all basic painting, with some “baked in” weathering, I applied a light coat of “CP30” (defined above) as a protective layer. Next came Tamiya Black Panel liner treatment on top, and Gray on bottom. Final selective “charring” effects were applied with AK RC 083 NATO black thinned about 30% to 70% High Compatibility Thinner over a series of Post-It Note masks, moving over the model in real time. Pressure and flow were dialed down here with just a quick pass of each area. Similar charring treatment was applied to the dark fuselage bottom in the same way using AK RC 289 RAF Medium Sea Grey. All was sealed with another coat of “CP30,” which provides a very pleasing and durable satin finish.

(All paints above were delivered by airbrush, powered by a CO2 tank with regulated pressure output: Primers and colors using Harder & Steenbeck Infinity with 0.2 mm tip, clears with H & S Evolution with 0.2 mm tip, and Metallics with AK airbrush and its standard 0.3 mm tip.)

All that remained was the installation of spindly landing gear and doors, and Kilroy lived again.

The achievements of Fulinya, Doolots, and the Kilroy team remained locked in a government vault until recently obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request. Although the Silbervogel spaceplane did not become operational, it certainly inspired a generation of designers to consider the many problems hypersonic flight and potential solutions. The later designs of the Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar, North American X-15, and Rockwell International Space Shuttle can all trace ancestry to this advanced 1930s concept, which secretly thundered over the New Mexico desert in 1947.

This article is dedicated to the memory of my friends Terry Moore and Stephen Tontoni, who delighted for many years in creating a series of spoof or “whiffer” builds with companion stories. During this Dia de Los Muertes (Day of the Dead) time of year, let us remember the great fun they provided us and continue their tradition.

Caption: (Left to Right) Fullovitt, Fulinya, and Doolots depicted following the second and final flight of Silbervogel “Kilroy”

References

Silbervogel (Wikipedia)

Saenger Antipodal Bomber (Encyclopedia Astronautica)

Operation Lusty (Wikipedia)

“The Pogo Experiment: Lindberg's 1/48 Convair XFY-1 Pogo,” Internet Modeler, April 1, 2009,

Terry Moore

“Jugs Over the Sinai; Israeli Thunderbolts,” Internet Modeler, April 2003, Chaim Joshen

“Miss Chiquita,” IPMS-Seattle Newsletter, February 2005 (p. 10), Tim Nelson

“A 1/48 1918 Fokker E.V Racer ‘Frieden’”, R.U. Schittenmee

Resources

Mission Models Paint

AK Interactive Real Colors Paint

Silhouette Cameo, available from the manufacturer, Micro-Mark, and other outlets.

For more on this review visit Modelpaintsolutions.com.

https://modelpaintsol.com/builds/the-sanger-antipodal-bomber-declassified-kilroy-revealed

Text and Images Copyright © 2023 by Tim Nelson

Page Created 2 November, 2023

Last updated

3 November, 2023

Back to HyperScale Main Page

Back to Reviews Page

|

Home

| What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search