|

How

To Apply Foil to an Aircraft Model

by

Bucky Sheftall

|

|

Republic

F-84 Thunderjet |

1.

The Answer to our NMF Dreams? |

Finding the

ultimate natural metal finish (NMF) technique has always been something of a

Grail Quest for The Hobby, perhaps akin to what discovering a cure for the

common cold is for medicine, developing a Grand Unified Field theory is for

physics or, until 1998 at least, belting more than 60 home runs in a season was

for baseball. Accordingly, false hopes have been raised many more times than

most modelers would like to remember. We have been teased and tempted over the

years by various products claiming to simulate NMF, mostly coming in paint

bottles, that never quite seemed to deliver as advertised. No matter how good

the results were, shiny paint is, after all, shiny paint and not aluminum, so

there was always that “close but no cigar” quality to even the best of

them.

Then,

of course, there have always been the countless “sure-fire” homespun

techniques for NMF that have made the gossip and BBS rounds over the years (“ya

gotta use organic sumac lacquer, mirror powder and yearling deerskin buffing

leather, but only during a full moon”, “dust it with Crisco and graphite,

then microwave the sucker”, “Electroplate”! Electroplate!”, etc., etc.).

Whatever the gimmick or trick, however, a real drop-dead, knock-your-socks-off

absolutely convincing NMF technique always seemed an unrealizable dream. Always,

that is, until recent years, now that a small but ever burgeoning number of

Fanatic Foil Freaks (FFFs) are working feverishly and diligently towards making

the dream a reality. Then,

of course, there have always been the countless “sure-fire” homespun

techniques for NMF that have made the gossip and BBS rounds over the years (“ya

gotta use organic sumac lacquer, mirror powder and yearling deerskin buffing

leather, but only during a full moon”, “dust it with Crisco and graphite,

then microwave the sucker”, “Electroplate”! Electroplate!”, etc., etc.).

Whatever the gimmick or trick, however, a real drop-dead, knock-your-socks-off

absolutely convincing NMF technique always seemed an unrealizable dream. Always,

that is, until recent years, now that a small but ever burgeoning number of

Fanatic Foil Freaks (FFFs) are working feverishly and diligently towards making

the dream a reality.

The

real kicker is that the answer to our prayers had never been farther away than

the nearest kitchen cabinet all along. With a little help from a two-buck bottle

of Microscale Foil Adhesive, all you need is a roll of cheap (the cheaper the

better – I’ll get into this later) aluminum kitchen wrap, a little practice

and a whole lotta patience to have show-stopping NMF aircraft models that will

dazzle friends and family alike. As a fellow FFF on another website has so

eloquently put it, “it looks like metal because it IS metal”. Well, that

says it all. Nothing looks more like aluminum than aluminum. Accept no

substitutes, folks.

OK.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that the technique is rather difficult,

always chancy and often exasperating. But then, when did that combination of

factors ever keep us from building models, right?

Cheap

aluminum kitchen or cooking foil, mirror-finished on one side, dull on the

other. You DO NOT want the good quality Reynolds Wrap kind of stuff Mom used on

those Christmas fruit cakes. No, that stuff is practically armor plate compared

with the aluminum foil I am using (Toyo Arumi – a product of resource-starved

Japanese manufacture), which has a thickness of 8 microns (less than most

painted surfaces). It is so flimsy it will rip if you look at it funny. Moral of

the story: cheaper quality is better because it is thinner, and the thinner the

foil you use, the better definition you are going to get to bring out all those

good rivets, panel lines, etc.

-

Flat

artist’s brushes about 1/2 inch in width. The quality issue is paradoxical

here, because while you want the brush to be supple enough not to leave

trench-deep brushstrokes in the adhesive backing, you must also steel

yourself to the sad fact that once you use one of these brushes in this

operation, you can never quite get all of the adhesive out of it, rendering

it fairly useless for other painting applications. Pliancy returns whenever

the brush is soaked in alcohol and/or used for more gluing, but it will

always dry to resemble something like a scale scuba flipper or rubber

spatula afterwards.

-

Microscale

Metal Foil Adhesive. Follow the instructions on the back of the bottle TO

THE LETTER! That should be explanation enough. The glue seems to be

acrylic-based, as its smell and color is similar to white woodworking glue.

It is water-thinnable, although I have tended not to exploit this property,

as I have encountered a lot of beading-up problems enough as is with the

surfaces I’ve been working with, and I think that thinning the glue would

only exacerbate this. But then again, my experience is still pretty shallow

with the material, and there is a lot more experimentation that needs to be

done. It seems likely that brushstrokes – which are often visible under

the foil after application to the model in the technique I am using now –

would be greatly reduced with thinner glue. In any case, the matter bears

looking into further. Microscale

Metal Foil Adhesive. Follow the instructions on the back of the bottle TO

THE LETTER! That should be explanation enough. The glue seems to be

acrylic-based, as its smell and color is similar to white woodworking glue.

It is water-thinnable, although I have tended not to exploit this property,

as I have encountered a lot of beading-up problems enough as is with the

surfaces I’ve been working with, and I think that thinning the glue would

only exacerbate this. But then again, my experience is still pretty shallow

with the material, and there is a lot more experimentation that needs to be

done. It seems likely that brushstrokes – which are often visible under

the foil after application to the model in the technique I am using now –

would be greatly reduced with thinner glue. In any case, the matter bears

looking into further.

-

Rubbing

alcohol. This is used to clean (as best as possible, that is) brushes and to

clean up dried patches of glue from botched model surfaces before

re-foiling.

-

Furniture

finishers fine-grit steel wool. Use the densest, thinnest strand wool you

can get. This is used not only in repair and botched surface clean up

operations, but also to apply the all-important finishing touch “patina”

of fine scratches over the foil surface to give your model a realistic NMF

sheen. After all, you want your plane to look like it is made out of

aviation Duralmin, not recycled funhouse mirror.

-

Cotton

swabs and round toothpicks. These are used in applying and burnishing foil.

The sharp tip of the toothpick is used to “revive” rivets and panel

lines after the foil goes on and the wrinkles have been rubbed out (often an

inexact science – but you have to learn to live with that).

-

A

plentiful supply of NEW single-edged razor blades and/or modeling/design

knife blades. Working with foil requires blades as sharp as possible.

Unfortunately, the foil also makes short shrift of any blade that comes into

contact with it, meaning that the half-life of your blade will be measured

in minutes. Literally. I went through about twenty razors and maybe half as

many design knife blades building the F-84.

-

And

last but not least, the “Three Ps” of foiling: patience, perseverance

and prayer. A little luck doesn’t hurt, either.

As Shep Paine

once put it, a metallic scheme is the most unforgiving surface type you can

model. Every mote of dust, every finger swipe, every hesitant brushstroke – in

short, every mistake you make with it will stand out as clearly and gaudily on

the finished product as cheap lipstick on a filling station bathroom mirror.

Although much more forgiving (if at least a bit more readily repairable) than

painted metallic schemes, foiling is still no exception to this rule, so keeping

the old adage about “an ounce of prevention” in mind and taking a few

prudent preparatory steps will save much heartache later on. First of all, it is

crucial that your work area be as dust-free as possible. A tall order, perhaps,

for a modeler, but a little preventive vacuuming or at least a peremptory

sweep-up or damp cloth wiping of your table certainly can’t hurt.

Addressing

the foil (“Hello, foil”…”To the moon, Norton, to the moon!”) is a

matter of careful and mutual respect between man and material. Cut a workable

amount of foil from the roll (i.e., just a little more than you need for the

area you will cover), taking care not to foul either your piece or the remainder

on the roll with small wrinkles. Big wrinkles can be rubbed out, but the small,

tight ones can not. If a piece gets wrinkled like this, it is unusable.

Lay

the foil dull side up (the matte finish provides “bite” for the glue, thus

minimizing beading) on a disposable, smooth, dust-free (sorry to be repetitive,

but I can’t emphasize this enough) surface. I’ve found dry cleaners’

shirt-backing cardboard to work nicely. Dip your brush about a quarter-inch into

the glue, then, making sure to keep your brushstrokes parallel (they’ll be

slightly visible after the foil goes on, so orient them to look like stress

lines or “grain” in the metal structure), start from one end of the foil

piece and brush evenly and quickly over to the other side, covering everything

in one pass. If either puddles or dry patches appear at this stage, you can (and

should) give them a quick stab or two with the glue brush, but you should do

this carefully, because as a rule of thumb, it is best not to go over the same

spot twice. The reason for this is that, much like uncured paint, the glue-wet

brush will re-liquidize spots from the previous coating, lifting them up and off

the surface as the brush passes over. These will then dry into little but very

inconveniently three-dimensional rubber cement booger-like motes that are

impossible to remove. If this happens, you will have to trash the piece, cut out

another and start all over again. Lay

the foil dull side up (the matte finish provides “bite” for the glue, thus

minimizing beading) on a disposable, smooth, dust-free (sorry to be repetitive,

but I can’t emphasize this enough) surface. I’ve found dry cleaners’

shirt-backing cardboard to work nicely. Dip your brush about a quarter-inch into

the glue, then, making sure to keep your brushstrokes parallel (they’ll be

slightly visible after the foil goes on, so orient them to look like stress

lines or “grain” in the metal structure), start from one end of the foil

piece and brush evenly and quickly over to the other side, covering everything

in one pass. If either puddles or dry patches appear at this stage, you can (and

should) give them a quick stab or two with the glue brush, but you should do

this carefully, because as a rule of thumb, it is best not to go over the same

spot twice. The reason for this is that, much like uncured paint, the glue-wet

brush will re-liquidize spots from the previous coating, lifting them up and off

the surface as the brush passes over. These will then dry into little but very

inconveniently three-dimensional rubber cement booger-like motes that are

impossible to remove. If this happens, you will have to trash the piece, cut out

another and start all over again.

If all has gone

well, you now wait until the whitish-milky glue has dried to a dull Scotch

tape-like sheen. I like to use my incandescent desk lamp as a dryer to speed

this process up. If you wish to do so, make sure you’ve dusted the lampshade

recently. If not, you’ll get a nice little sprinkling on your glued foil when

you adjust the light over the work area.

Once

the pressure sensitive glue has dried, the foil is ready to be applied. Choose a

single point near the center of the area to be foiled, and aim center-of-mass of

your foil piece to touch there and ONLY there. From this single, central point,

begin burnishing out towards the edges, being careful not to make any more

wrinkles than you absolutely have to. After you have finished burnishing and

find, to your horror, that there are nasty little air blister bubbles in the

foil, just lance’em! Make a feathery light cut along the bubble from end to

end, with just enough pressure to cut the foil but NOT the plastic underneath.

Burnish over this with the edge of a toothpick, pushing along the same direction

as the cut, and it will all but disappear.

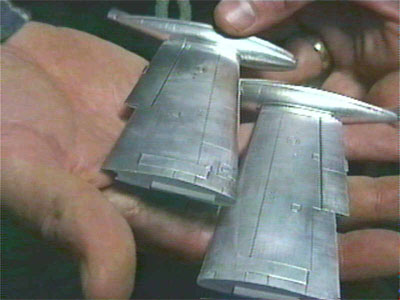

Before beginning

any foiling, you should study the layout and structural scheme of your model to

determine the order in which you will foil. In general terms, when working with

aircraft, I have found it best to foil fuselage, wings, stabilizers and (if

present) drop tanks separately before assembly.

Foiling each

distinct airframe component like this keeps your foil pieces small and

manageable, reducing hassle in the event of “disaster” requiring re-foiling

and also helping to prevent wrinkles and spindles by avoiding abrupt angles

(wing joints, etc.) in the surfaces to be foiled.

The

particular machine I chose to model is 1LT Dolphin Overton’s fighter bomber

stationed at Taegu, Republic of Korea in 1951. Lieutenant Overton was a 1949

graduate of West Point who was commissioned in the new Air Force and later went

on to ace status in F-86 Sabres. Aeromaster produces fine quality decals (AM

48-408 and stencil set AM 148-025) for modeling this aircraft.

|

As

goes without saying for anything recent from the House of Tamiya, the

model itself went together without a hitch. Fit was flawless everywhere.

In addition, the lack of irregularly curved surfaces makes this airframe a

good starting project for the beginning foiler, with the only notable

exception being the wingtip and fuselage drop tanks, which are shaped like

something out of a calculus textbook and present a MAJOR foiling

challenge. As

goes without saying for anything recent from the House of Tamiya, the

model itself went together without a hitch. Fit was flawless everywhere.

In addition, the lack of irregularly curved surfaces makes this airframe a

good starting project for the beginning foiler, with the only notable

exception being the wingtip and fuselage drop tanks, which are shaped like

something out of a calculus textbook and present a MAJOR foiling

challenge.

|

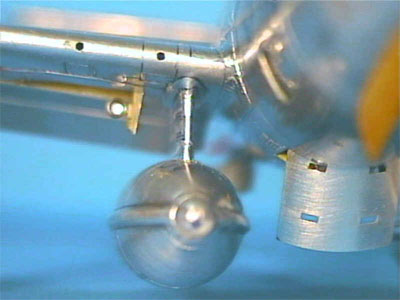

The

best advice I can give for working with these is to keep your foil

sections small, manageable and parallel, because joints in the foil on

these curved surfaces are rather conspicuous, so it’s best to make them

look like they are supposed to be there. Liberal uses of parallel steel

wool strokes will help a lot in masking the joints. If done well, this can

render them almost (emphasis on “almost”) invisible (PIC 3), not only

in the fuel tank construction but in foiling any area on the aircraft. The

best advice I can give for working with these is to keep your foil

sections small, manageable and parallel, because joints in the foil on

these curved surfaces are rather conspicuous, so it’s best to make them

look like they are supposed to be there. Liberal uses of parallel steel

wool strokes will help a lot in masking the joints. If done well, this can

render them almost (emphasis on “almost”) invisible (PIC 3), not only

in the fuel tank construction but in foiling any area on the aircraft. |

| Eduard etched parts were

used in this model. One nice feature of this set is that it provides you

with an early-type speed brake panel, which you will need if you are

modeling a Korean Conflict-era aircraft. The “swiss cheese” speed

brake panel provided by Tamiya is for mid-50s, post-Korea Thunderjets

(opposite chronology appears in Squadron/Signal’s “F-84 Thunderjet In

Action”, proving that it sometimes pays to be wary of your sources!).

|

OD

anti-glare, yellow trim, cockpit green and yellow zinc chromate are all

done in Model Master acrylics. Now that we are on the subject of paint,

one somewhat unfortunate characteristic about foil is that it takes to

most paints like Teflon takes to scrambled eggs. I found this out, to my

chagrin, when my entire OD anti-glare panel lifted off in one clean,

contiguous piece along with the masking tape I was peeling off. After a

few moments of dire panic, cooler sentiments prevailed and I reached for

my trusty bottle of floor wax. Subsequent experimentation revealed that

this was the only medium compatible with the foil to any kind of

dependable degree, but that at least TWO rather heavy-handedly applied

coats of this were needed before paint could go on and stick. For some

reason, however, decals went straight on the bare foil without any peeling

or any other problems. OD

anti-glare, yellow trim, cockpit green and yellow zinc chromate are all

done in Model Master acrylics. Now that we are on the subject of paint,

one somewhat unfortunate characteristic about foil is that it takes to

most paints like Teflon takes to scrambled eggs. I found this out, to my

chagrin, when my entire OD anti-glare panel lifted off in one clean,

contiguous piece along with the masking tape I was peeling off. After a

few moments of dire panic, cooler sentiments prevailed and I reached for

my trusty bottle of floor wax. Subsequent experimentation revealed that

this was the only medium compatible with the foil to any kind of

dependable degree, but that at least TWO rather heavy-handedly applied

coats of this were needed before paint could go on and stick. For some

reason, however, decals went straight on the bare foil without any peeling

or any other problems. |

The

fundamental weakness inherent in foiling is the simple, physical fact that

you are trying to cover three-dimensional, often irregularly curved

surfaces with an inherently inflexible two-dimensional medium. The most

obvious and commonly occurring consequence of this dynamic is, yes, you

guessed it, wrinkles. I should re-emphasize this by saying that, more than

just commonly occurring, wrinkles are downright unavoidable in foiling.

Now, you can either let that fact break your heart and give up the whole

project, or you can push on and face up to those wrinkles (ha-ha) using

any – or any combination of – the following options: The

fundamental weakness inherent in foiling is the simple, physical fact that

you are trying to cover three-dimensional, often irregularly curved

surfaces with an inherently inflexible two-dimensional medium. The most

obvious and commonly occurring consequence of this dynamic is, yes, you

guessed it, wrinkles. I should re-emphasize this by saying that, more than

just commonly occurring, wrinkles are downright unavoidable in foiling.

Now, you can either let that fact break your heart and give up the whole

project, or you can push on and face up to those wrinkles (ha-ha) using

any – or any combination of – the following options:

|

-

Ignore them.

-

Go over them again and again

with a cotton swab or other tool and try to burnish them away.

-

Sand them into oblivion with a

silicon disc, etc., then lay small foil panels over the areas where the foil

has been removed.

-

Cut out the affected area, then

foil over it.

-

Consult a good plastic surgeon

(ha-ha)

Before

I forget, I should note here that there are two basic schools of thought

regarding foil jointing. One (and perhaps the dominant) school holds that the

best results are to be had by foiling along the panel lines, i.e., laying each

panel with a separate piece of foil, then cutting away the excess. The major

plus for this process is that does it away with the need for overlapping foil

joints. The downside of this is that the foil edges are delicate, and when you

go back to blacken the panel lines later on, you will inevitable curl up some of

these edges, sometimes requiring major repair. Also, this process involves

freehand blade cutting directly on top of the plastic. I don’t care how good

of a brain surgeon you may be, there is just no way that you are going to leave

those panel lines the way you found them after you have gone over them with an

X-acto knife. The damage may be minimal, but it is there, and if your

personality is anything like mine, it will bother you later on just knowing that

it is there, and will catch your eye every time. Before

I forget, I should note here that there are two basic schools of thought

regarding foil jointing. One (and perhaps the dominant) school holds that the

best results are to be had by foiling along the panel lines, i.e., laying each

panel with a separate piece of foil, then cutting away the excess. The major

plus for this process is that does it away with the need for overlapping foil

joints. The downside of this is that the foil edges are delicate, and when you

go back to blacken the panel lines later on, you will inevitable curl up some of

these edges, sometimes requiring major repair. Also, this process involves

freehand blade cutting directly on top of the plastic. I don’t care how good

of a brain surgeon you may be, there is just no way that you are going to leave

those panel lines the way you found them after you have gone over them with an

X-acto knife. The damage may be minimal, but it is there, and if your

personality is anything like mine, it will bother you later on just knowing that

it is there, and will catch your eye every time.

The

method I prefer is to live with joints in peaceful co-existence (thus nicely

preserving the integrity of my panel lines). In other words, I try to cover as

much surface with one piece as I can while keeping the size manageable and

deliberately avoiding laying the edges along panel lines. Despite its thinness,

foil is amazingly tough and resilient under abrasives, and I use this quality of

the material to maximum advantage in employing abrasives and buffing agents to

hide joints.

In

any case, experiment with an old model to find a technique that works for you.

|

On

a related and final note, dealing with sharp edges like trailing wing

edges and control surfaces presents another choice of technique. One

technique, which is the easier but, as I have discovered, far less

satisfactory of the two is to simply foil out to the end of the edge and

just trim away the excess. This may look fine for a while, but after even

the slightest handling, the edges are in dire danger of curling up. If

that starts to happen, all you can do is to keep mashing them down or to

keep cutting away, hoping that the process will eventually stop before

you’ve denuded the entire aircraft. On

a related and final note, dealing with sharp edges like trailing wing

edges and control surfaces presents another choice of technique. One

technique, which is the easier but, as I have discovered, far less

satisfactory of the two is to simply foil out to the end of the edge and

just trim away the excess. This may look fine for a while, but after even

the slightest handling, the edges are in dire danger of curling up. If

that starts to happen, all you can do is to keep mashing them down or to

keep cutting away, hoping that the process will eventually stop before

you’ve denuded the entire aircraft.

An

overlapping technique is by far more effective in producing durable and

convincing edges. Foil the upper surfaces clean over the top and around to

the bottom, where you can joint in a fairly inconspicuous spot under the

aircraft. A little touch up with your trusty sanding tools and some elbow

grease with the steel wool again and you’re in business. |

Foiling,

obviously, is not for everyone. The average modeler, with an average

patience limit, would be better off sticking to the trusty airbrush and

investing in a bottle of SnJ (which is supposed to be excellent, I

understand). For this author and the slowly, slowly burgeoning ranks of

FFFs, however, nothing looks more like aluminum than aluminum, and even

with its significant flaws, foiling can not be bested in simulating

Duralmin NMFs in scale aircraft modeling. Let the results speak for

themselves: Foiling,

obviously, is not for everyone. The average modeler, with an average

patience limit, would be better off sticking to the trusty airbrush and

investing in a bottle of SnJ (which is supposed to be excellent, I

understand). For this author and the slowly, slowly burgeoning ranks of

FFFs, however, nothing looks more like aluminum than aluminum, and even

with its significant flaws, foiling can not be bested in simulating

Duralmin NMFs in scale aircraft modeling. Let the results speak for

themselves: |

Click the

thumbnails below to view images full-sized.

Click the "Back" arrow on your browser to return to this page.

Visit

Bucky's Website at

www.geocities.com/TimesSquare/Alley/6207

-

Tamiya

1/48 F-84G Thunderjet

-

Aeromaster

decal sets “Thunderjets Over Korea, Pt.II” AM 48-808

-

And

“F-84 Stencil Set” AM 148-025

-

Eduard

photoetched parts set #48257for TAM F-84G Thunderjet

-

Microscale

Foil Adhesive

-

Toyo

Arumi aluminum foil

Model, Text and Images Copyright ©

2000 by Bucky Sheftall

Page Created 05 April, 2000

Last Updated 26 July, 2007

Back to HyperScale Main Page

Back to Reference

Index |

Home

| What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search