|

|

|

F-14A

Tomcat |

Hasegawa's

1/48 scale F-14A Tomcat and

Black

Box's F-14D replacement cockpit

are available online from Squadron.com

In this day of after market resin

cockpits for every new kit to be released, finally someone has started

paying attention to the kits that are not so new, but just as deserving

of the attention. The company is called Black Box. They have

begun releasing a series of full resin replacement cockpits for a number

of great older kits including Revell's A-6E, Hasegawa's

"Teen Series" (F-14A/D, F-15C/E, F-16B/C, and F-18C/D), Monogram's

"Century Series" (F-100D, F-101B, F-102A, F-104G, and F-105G),

and more. All of these kits are great kits in their own right, but some

of them are pushing 20+ years old and are starting to show their age in

the lack of state-of-the-art details. These Black Box cockpit

sets are just what the doctor ordered to give these kits a real lift.

The Hasegawa F-14 kit has been

out for over 15 years. Built out-of-the-box, it makes a very respectable

model of the Tomcat. The timing of the release of the Black Box

F-14 cockpit set could not have been better as I had just started work

on some Hasegawa F-14 kits. It was a natural to want to use the

cockpit set in these models I was just starting to build. While I had

already gone to the trouble of fixing Hasegawa's cockpits pieces

to better fit the kits, I had not done any extensive detailing or

painting, yet. So, I tossed the kit cockpits out the window and decided

to use Black Box cockpits instead.

I acquired my Black Box F-14

cockpits within days of seeing one at a friend's house. I've seen many

resin cockpits, but the level of detail in this Black Box set

took my breath away. I could not believe the wealth of details that it

provided, on the instrument panels, on the side walls, on the back

walls, and even on the floor! And, I could not wait to have a cockpit

set for my very own. As I was actually working on three Hasegawa

Tomcats simultaneously, I acquired three of the set. Then, I acquired a

couple more sets to put away for future projects. After all, you can

never have too many detail sets.

Black

Box Tomcat Cockpit Set

|

All the Black Box cockpit sets

are marketed in hinged plastic boxes. Packed neatly inside the F-14

cockpit set box are twenty pieces of resin. One is the large cockpit

tub, wrapped in a piece of foam. The rest are all the detail pieces to

attach to and around the cockpit tub. These are contained loosely in a

small zip-lock storage bag. Because some of the resin pieces are molded

with two pieces together, the actual part count for the detail set is

twenty-six. There is no piece of the original kit used inside the

replacement cockpit from Black Box.

A small folded instruction sheet and the

front cover artwork page finish out the packaging. The instruction sheet

is a single exploded view drawing of the entire cockpit set. On the

backside of the paper are text instructions outlining the process to

modify the Hasegawa kit for the replacement cockpit. Where Black

Box excels at resin, they are somewhat lacking on making clear

instructions. I have included pointers in this writing to help clarify

the proper placement of some of the pieces. Read on...

The parts are numbered in the directions

from 1 to 18. They break down as follows:

- #1 is the main cockpit tub.

You have to see this tub to appreciate it. There is detailing just

oozing from every corner of this piece. This includes not only the

instrument panels, but also the area below the instrument panels, on

the rear walls, and up where the pilot's feet would rest. The floor

of a Tomcat is not just a flat slab. This tub correctly captures the

stepped floor.

- #2, #3, and #4

assemble together to make the ejection seats. There is two of each

part. #4 is the rocket tube that attaches to the rear of part #2

(the seat). I am unsure why they made this separate from the seat.

The amount of flash on part #3 (the overhead ejection rings) was

going to be a nuisance to remove without breaking the pieces, so I

replaced these pieces with the ejection rings from the kit. The kit

ones looked as good and were flash-free. While cutting free the kit

ejection rings, I also cut free the lower ejection ring that goes

between the pilot's (or RIO's) legs. Black Box missed these

items in their set. My only real complaint is that the seats have

nearly identical seat belt layouts. They are different from each

other, but the difference is not pronounced enough in my opinion.

This is especially true for the shoulder harnesses on the seat

backs.

- #5 and #6 are the front

and rear main instrument panel hoods (respectively). Each has the

upper main instrument panel instrument details molded into the rear

side. #7 and #8 are the lower portion of the front and

rear main instrument panels (respectively).

- #9(L/R) and #10(L/R)

are the front and rear side wall detail pieces. These are

wonderfully detailed and correct. They are also sorely needed as the

Hasegawa kit has no molded side wall detailing.

- #11(A & B) assemble the

make the front control stick. These are extremely fine and a little

tricky to assemble. I needed to check my Tomcat documentation to be

sure I got them assembled the correct way.

- #12 is the center pedestal for

rear cockpit holding the RIO's radar control grip.

- #13 (2 pieces) are the front

rudder pedals.

- #14 (2 pieces) are the rear

cockpit floor footrests. They mount on the rear cockpit floor with

the short side down. The instructions do not label them as left and

right, but they do have a left and right placement. Looking at them

closely, there is a small dimple in the upper corner of each. These

rests hold the RIO's microphone and intercom switches and that

little dimple is the actual switch on each footrest. The dimple on

each foot rest should be on the inboard sides of the rests when they

are mounted to the cockpit floor.

- #15 and #16 are various

cockpit details that should have been molded in place in the cockpit

tub but were not. Attach them as shown in the instructions, although

the location of part #16 is not real clear. I decided to leave it

off, as the rear wall of the rear cockpit (where the instructions

seem to indicate it goes) had no real place to put it. I felt that

leaving it off was safer than putting it in the wrong location.

- #17 is the rear decking in the

back of the cockpit, where the canopy hinge is located. The

instructions say to use a piece of the Hasegawa kit to create

the lifting plunger for the canopy. For added strength, I decided to

use comparably sized brass wire for this part.

- Lastly, #18 is the pilot's

throttle control. Black Box kindly molded

"protectors" into the slag of this part to help keep the

fine "neck" portions from being broken off in the

packaging. Trouble is, they are so fine that I broke them the first

time a handled the part after removing it from the slag. A better

approach is to just remove the "necks" and drilling some

small holes in the part. Then use some fine brass wire to mount the

part and represent the "neck" of the throttles. I used

some .005" brass wire for the job.

You can check out various F-14 cockpit

photo reference pages for more details concerning the accuracy of this Black

Box set. I posted an extensive set of Tomcat cockpit pictures in the

Walk Around section of ARC.

But, take my word, the set is extremely accurate. At the time I was

working on these Tomcat cockpits, I spent an entire morning

photographing the cockpit of a real F-14A. I was amazed at the level of

accuracy in this Black Box cockpit set.

I have read many kit construction

articles over the years where the author states he/she used some resin

cockpit in the model being discussed. But, they don't often elaborate on

that point. When they do mention some of the construction involved with

the resin cockpit, it is usually buried in the rest of the text and hard

to find. I wanted to write something more about just the construction

and usage of the resin, itself. For a complete review of the

construction of my Tomcat(s), look to future postings dedicated to them

where I only mention their resin cockpits in passing.

The first trick to any resin set is to

remove the resin parts from their sprue, also known as slag.

I use one of four ways to accomplish this task.

- Sand Paper and Elbow Grease -

Lay sand paper on a flat surface (gritty side up) and rub the resin

part on the paper to sand off the slag. A friend of mine uses a belt

sander to accomplish this task. Where I might spend twenty minutes

on a part using sandpaper, he spends twenty seconds. Beware, though,

the belt sander is so fast that overdoing the sanding is real easy.

Make sure you are in control of the part and constantly check to see

when you have removed enough slag from the part. Dust control is

also a big concern using the belt sander.

- Scribe, Bend, and Break - With

a "scribing tool" or an X-acto knife, score a line

along the edge of the detail part. Then, gently bend back on the

slag. Resin is usually rather brittle and the scored line acts as a

weak point in the resin. The part snaps free along the scribed line.

Depending on the thickness of the slag, you may need to run the

"scribing tool" or X-acto knife along the part

several times to make a deep enough score line to insure the slag

breaks off cleanly.

- Saw Blade - Using one of

several styles of saw, cut the parts free of the slag. I make use of

all the following at different times for different tasks -- an X-acto

razor saw, a Dremel radial saw, and a jeweler's saw.

- Carving - Each of the previous

three methods assumes there is a straight edge for the slag to be

removed along. Occasionally, a detail set will have a piece that is

not straight on any side and therefore can not be attached to the

slag with a straight edge. When this happens, your only real choice

is to get out your trusty X-acto knife with a #11 blade and

start carving off the slag along the needed line.

Each of these ways is tailored to a

specific type of slag removal. I used all of the first three ways of

slag removal to work on this cockpit set. None of the pieces in this Black

Box set required the fourth style. Each of these ways is a bit

tedious and prone to trouble, so I will try to elaborate more about them

as I go.

The first method, sand paper and

elbow grease, is used when removing large amounts of slag from the

bottoms of large pieces, specifically the main cockpit tub in this set. Black

Box was nice in providing a clue to how much resin needs to be

removed as they have a molded in line running around the outside bottom

of the main cockpit tub. I needed to sand the bottom until this line is

reached. Sounds easy, huh? Guess again.

I start by laying down a piece of heavy

grit wet-and-dry sandpaper on a flat surface, grit side up. I use 180

grit paper. Finer grit takes too long to sand and heavier grit leaves

too rough of a surface when I am done. I regularly clean the paper as I

am working to remove the resin residue, brushing it into the trashcan.

This residue gets under the resin piece and interferes with the sanding

if I just leave it alone. Also, some of the residue can get ground into

the paper and form a smooth surface on the paper. A scrape from an old X-acto

blade removes this crusted residue and allows the sandpaper to continue

its job.

|

There are two choices here -- sanding

wet or sanding dry. Particles in suspension making the

sanding go faster is bull-cr*p, so do not make any decision on those

grounds. It simply comes down to dust control and the messiness of the

task. Wet is not dusty, but it is very sloppy. Dry is less sloppy, but

is very dusty. Bear in mind while you are deciding, too, that resin dust

is a cancer-causing agent. Get a hold of a safety placard for the stuff

sometime and then turn white when you think of all the times that you

have breathed this stuff while modeling.

Anyway, I prefer the dust to the slop.

So, I sanded the cockpit bottom dry. To keep from breathing the dust, I

did the sanding in my paint booth. Like the fan removes the paint fumes,

it also removes the resin dust in the air. I also wear a dust mask to

protect me from anything the paint booth fan missed. I move the resin

piece in a small circle on the sandpaper, taking care to consciously

watch how hard I press on the piece. I needed to continuously check and

recheck the line running around the cockpit tub to see when I was

finished. All three of my cockpits were molded with more slag on one

side. This presents a challenge to control my pressure on the piece and

sand only one side without letting the other side lift off of the

sanding surface. I also needed be careful not to rock the piece as I

moved it on the sandpaper. Rocking the piece would cause a non-flat

bottom on the piece and complicate mounting it squarely on the nose

landing gear well.

That last sentence brings me to the real

pitfall of this sanding process. If I remove too much resin, the cockpit

sits too low in the fuselage and can complicate the interaction of the

other pieces of the set that are counting on the cockpit sills to fall

at just a certain height. If I don't remove enough resin, the cockpit

will not fit into the fuselage at all. With practice, this all can be

mastered, honest! It just takes time and practice, practice, practice...

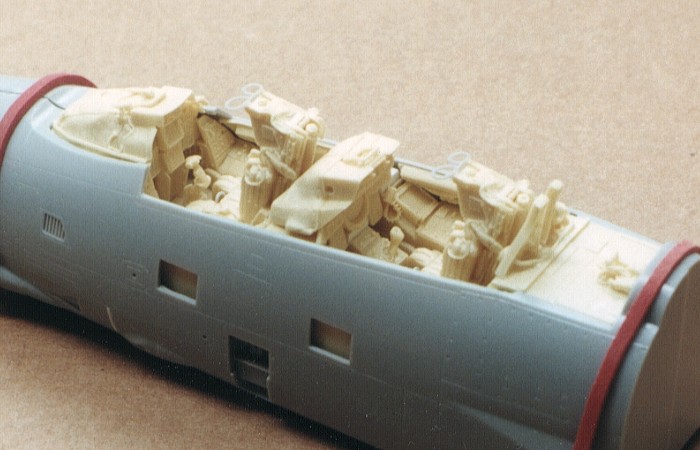

With the cockpit sanding done, I needed

to turn my attention to the kit fuselage. The Black Box

instructions say to remove some interior portions of the fuselage side

to make clearance for their cockpit pieces. See the pictures to the

right. The one shows what I needed to remove and what it looked like

after removal. The other picture shows the view from the outside with

the Black Box cockpit fitted inside the fuselage. The side of the

resin cockpit replaces the portions that were cut out of the fuselage.

An alternate approach that a friend of

mine used on his Black Box set would be to machine out holes in

the side of the Black Box cockpit piece. The holes fit over the

things inside the Hasegawa fuselage that Black Box is

saying to remove. The decision comes down to which way you are most

comfortable at working and what tools you have available to do the work.

With the cockpit bottom sanded and the

fuselage modified, I assembled the kit nose wheel well and tacked it

onto the cockpit bottom with a small dab of super glue to test the fit

inside the fuselage. When I was satisfied that the fit was correct and

the wheel well placement was correct, I applied liberal amounts of super

glue and accelerator to firmly attach the cockpit to the nose wheel

well. Note that normal plastic cement will not work on resin. Super glue

is the least messy way to deal with attaching resin parts to each other

and the styrene kit parts. Two-part epoxy can also be used, but that is

more mess than I ever want to get into unless I am left no choice.

|

With the cockpit position finalized, I

could turn my attention to the next items in the assembly. For me, these

were the side walls. These are molded with the slag running down a very

thin edge. The method I use for removing this type of slag is the scribe,

bend, and break method. I use a Squadron scribing tool to

score a line down the edge of the piece. Depending on the thickness of

the slag, I may retrace the scribed line repeatedly to make a deep

groove. In the case of these side wall pieces, repeated passes of the

scribing tool was not needed. The scribed line acts as a weak point in

the resin and by gently bending the slag back from the scribed line, it

snaps. This is generally a pretty clean break, but I will use an X-acto

knife and/or file to finish off the resin part and make the edge smooth

and regular.

I then assembled the fuselage with the

cockpit in place and rubber banded the fuselage together. Verifying the

cockpit was positioned correctly, I tacked the side wall pieces into the

fuselage interior with a small dot of super glue. Some of the side walls

are a bit large for the cockpit areas they fill. I needed to trim them

down a little on their ends to make them properly fit in place. When all

the side walls were in place and I was certain they were correctly

located, I carefully disassembled the fuselage and applied more super

glue to firmly attach the side walls.

With all the side walls installed into

the fuselage, I started work on the detail pieces that needed to be

added into the cockpit tub. There are quite a few details to be trimmed

off of their slag and added inside the cockpit tub. A few of these left

me scratching my head and wondering. They could easily have been part of

the main tub when it was cast. That would have eliminated my need to add

them (and potentially mess them up).

Most of the detail pieces come attached

to solid slag blocks in one way of another. I find the saw blade

approach works best at removing pieces from slag that are attached in

this manner. For very tiny or fragile pieces, I find the best saw for

the job is my Dremel high-speed motor tool. I mount a tiny radial

saw blade in the tool and carefully cut the parts free of their slag. I

have found that this style of cutting provides the most accuracy on the

cut with the least chance of damage to what can be very fragile pieces.

Of course, this cutting is not without

risk. Dremel stopped selling this saw blade after a few

unfortunate people lost fingers using it. The blade is extremely

effective at cutting any soft material, including skin and bone. Take

precautions when using this tool/blade combination. If the blade binds

up and jumps, do not have any fingers in its way. A saw blade to fit

your Dremel tool is still available from companies other than Dremel.

Once the pieces were cut free of their

slag, I attached them into the cockpit tub in the locations indicated on

the instruction sheet. See the descriptions with the individual parts

(above) for any specific notes regarding the placement of the detail

parts within the cockpit tub.

In the case of the main instrument

panels, I assembled the rear panel (parts #6 and #8) and left the rest

as separate pieces (parts #5, #7, and #12). I kept these out of the

cockpit tub pending the completion of the painting of the parts. On dry

fitting the pieces into the cockpit, I found the rear instrument panel

sat too flat in the cockpit tub. So I added .060" strip

styrene at the place where the rear portion of the panel rested. This

had the effect of rocking the instrument panel so that the instruments

faced the RIO's face, not his belly button.

|

The final things to assemble after the

detail parts were all attached into the cockpit tub were the ejection

seats. Here I also used the saw blade approach to slag removal.

This time, though, I used an X-acto razor saw. This style of

cutting is better than the Dremel cutting method for larger

pieces like the seats as the slag portions are larger and more prone to

binding the Dremel blade. I like my fingers attached to my hands

where they are, so this less volatile cutting method works better. Also,

the seats are more regular in shape and can be held without as great a

chance of breaking them.

With all the seat pieces free of slag, I

assembled the seats and placed them aside to wait for painting.

When I completed assembling the ejection

seats, I was done with the integration of the Black Box set into

the Hasegawa F-14 kit. All that was left was painting the

details, but that will be a different posting.

As I said at the start of this article,

it is about time that some manufacturer pays attention to these older

kits. Black Box definitely has their act together and is

producing some of the best after-market cockpit detail sets I have had

the privilege to use. I hope to see them continue to grow their line.

Go

to Part Two - Painting the Cockpit for Effect

Go to Part Three - Tomcat Construction

Go to Part Four - Painting an NSAWC Tomcat

Model, Description and Images Copyright ©

2001 by David Aungst

Page Created 27 June, 2001

Home

| What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search