Mikro Mir 1/48 scale

DH.88 Comet "Grosvenor House"

by Roland Sachsenhofer

|

DH.88 Comet "Grosvenor House" |

The centenary celebration of the Australian state of Victoria, a wealthy chocolate manufacturer, an innovative aircraft manufacturer and a national aviation industry that had a lot of catching up to do: these are the essential ingredients from whose interaction the aerodynamic beauty presented here in the model emerged. A beauty that, in combination with its performance, has ensured lasting fame: even if not everyone will know its name, the DeHavilland Dh.88 Comet is still a well-known icon even today!

The Victorian Centenary Air Race (MacRobertson Air Race)

What role do the factors mentioned at the beginning play? Sir Macpherson Robertson, a wealthy businessman and manufacturer of chocolate ("MacRobertson's confectionery") had donated the considerable sum of 75,000 US dollars to the 1934 centenary celebrations of his home state of Victoria. The sum was earmarked for the organisation of an 18,500-kilometre air race from Great Britain to Melbourne. The Shell Group also agreed to supply the necessary fuel, while the British Royal Aero Club took over the complex organisation of this half-planet race. The start was announced for 20 October 1934, and the flight route would take participants from RAF Mildenhall in England, through France, the Mediterranean, the Middle East, Afghanistan, India, Sumatra, Batavia and Timor to Melbourne in Australia. 27 airfields along the route were prepared for the competition, some of which had to be upgraded for the purpose.

The conditions of the competition are revealing: in principle, all aircraft were eligible to take off that could present a valid air safety certificate and proof that they met the requirements of the International Convention of Air Navigation (ICAN). There were no requirements regarding the number of engines, crew size or construction. The only further regulation was that once the aircraft had left British airspace, the crews could no longer be changed. These very open requirements probably also explain the strikingly wide range in size, crew size and engine size of the participating aircraft.

As competitors of the DH.88 Comet the best and most efficient proponents of the passenger, sports and racing aviation of the time. Two special constructions were quickly considered favourites by the participants: a four-man Dutch team took part with one of the new DC-2 from Douglas, while a three-man US crew entered a Boeing 247, which, along with the DC-2, was considered one of the most modern passenger aircraft of the day. The list of participating aircraft also includes other well known names such as Lockheed Vega, DH. 98 Dragon Rapid or Miles Hawk Major.

The American favourites were bursting with modernity and had already earned their merits - in contrast to the Dh.88 Comet, of which no plans even existed at the time the competition was announced. In fact the three participating DH. 88 Comet were built within the astonishingly short period from January to October 1934. The final modifications literally dragged on until the last days before the launch. How did it come about?

The De Havilland DH.88 Comet

Against the background of an emerging technical superiority of US designs, concern began to spread in Britain about an extremely disgraceful race outcome. DC-2s, like Boeing 247s, were fast, lightweight aluminium machines with retractable undercarriages, self-supporting fuselage panels and cleanly cowled engines that had left the antiquated design of British biplane passenger planes far behind. Until then, Britain had nothing that could compete with the Americans.

De Havilland was aware that its own competing designs, the DH.86 Express, a fabric-covered four-engined biplane, and the DH.80 Puss Moth, a sports and cruising aircraft, would not finish the race in a winning position. However, they were confident that they could fundamentally change things with a completely new design! Self-confidence was also evident in the way Their new race participant was announced: in January 1934, barely ten months before the start, De Havilland published the following advertisement: for a price of 5000 pounds, one could purchase a new De Havilland racing aircraft; the design, engine or performance parameters were still unknown, only the delivery date and the speed-promising name of the new aircraft were guaranteed: Comet.

Indeed, interested parties and soon buyers were found immediately: the aviator couple Jim Mollison and Amy Johnson, dubbed "flying sweetharts" by the press, were the first to sign, followed by A.O Edwards, owner and director of the Grosvenor House Hotel. As De Havilland was only prepared to build the Comet if three or more aircraft were ordered, the subsequent wait for a third buyer was nerve-wracking: the end of the registration period was approaching inexorably. There was great relief, therefore, when a third buyer was finally found in the shape of the well-known racing driver Arthur Ruben. By the way: De Havilland calculated the guaranteed purchase price of 5000 pounds at about one tenth of the actual cost per machine. In the event of a victory, this sum would be well invested not only through the experience gained, but also as advertising.

De Havilland had long been cagey about the construction of the new aircraft, but internally, chief designer A.E. Hagg was quickly certain that the goal would not be a copy of the light metal constructions, but a construction method that he personally knew well from building racing boats: the Comet would be made as a carefully shaped plywood construction. Plywood fuselages and wings have characterised De Havilland designs ever since; the legendary DH.98 Mosquito is just one example.

The choice of engines for the Comet was also quickly decided. Just in time as it seemed, De Havilland's engine specialist Frank Halford had developed a new six-cylinder variant of the companys proven Gipsy Major. Two tuned "Gipsy Six" were deemed to be an ideal drive for the new racing aircraft.

De Havilland supplied the three Comets in three different colours. The first aircraft was that of the Mollisons: this DH.88, number 1994, was effectively the prototype of the small series. On 8 September 1934, it was taken into the air for the first time by test pilot Hubert Broad. With the high-performance design pushed to the extreme, it was no wonder: numerous modifications had to be made until shortly before the race start. On the morning of 20 October, however, the machine was ready: painted glossy black, it stood tall at the start with the inscription "Black Magic" and the registration G-ACSP.

Edwards Comet was launched with the designation G_ACSS as "Grosvenor House". Edwards had engaged the renowned pilots C:W.A. Scott and Tom Campbell Black as crew. It will probably no longer be possible to ascertain why the colour red was chosen. Whether the explanation handed down by Scott's wife Greta that this was decided by the colour of one of her cocktail dresses really explains anything is for the reader to decide.

The colour of the third Comet, on the other hand, is easier to deduce: Bernard Rubin was a well-known racing driver, and his choice of colour was, sensibly enough, the "British Racing Green" familiar from motor racing at the time. Rubin had planned to get into the cockpit with fellow aviator Ken Waller, but it was to be to his chagrin: taken ill shortly before the race, he had to find a replacement for himself: Owen Cathcart-Jones was fortunately to prove a good choice. Rubin's machine was the third Comet at the start in splendid "Racing Green" and with the registration G-ACSR. No name was given, and the nose remained empty except for a small Union Jack.

The three Comets finished the race in quite different ways.... "Black Magic" took the lead on the first day; the Mollisons flew non-stop to Baghdad and, flying on quickly, set a new record for the London-Karachi route. However: after take-off in Karachi, their luck seemed to turn away from them: first, the landing gear would not retract. Return and subsequent repair cost valuable time, made worse when Jim Mollison forgot the chart on the ground during the hectic take-off. Their luck was now to turn completely away from them. On the way to Allahabad, they got so thoroughly lost that they had to make an emergency landing near Jabalpur with empty tanks. After they had actually managed to organise fuel for them, the end came for the two when they next landed in Allahabad. The fuel, suitable for running bus engines, should never have got into the tuned Gipsy Six engines. With seized pistons, G-ACSP "Black Magic" had to abandon the race.

There were also hairy moments for G_ACSS "Grosvenor House". After they had been very well in the race for a few days, it suddenly looked like an early race end for Scott and Black as well: over Darwin, an engine had to be stopped after the oil pressure had fallen below the limits. After a De Havilland mechanic who happened to be present found the problem in the form of a clogged oil filter, the onward flight was saved. Despite continuing problems with the engine - and a failed propeller adjustment mechanism - the two managed to achieve the best performance they had hoped for: A.O. Edwards' "Lady in Red" had won the Victorian Centenary Air Race, the MacRobertson air race!

The story of the third Comet, Ruben's green G_ACSR, is also exciting. Here the repairs began before the race: during the fly-in at Mildenhall on the day before the race start, a propeller was bent during landing. The mechanics slaved through the night and managed to straighten the bent blade tips just in time to secure the start of G_ACSR. Throughout the race, the machine and the crew performed excellently, finishing in a respectable fourth place. However, the green G_ACSR really made history afterwards. The day after the race, Cathcart-Jones and Waller took off for the return flight to England, the conical nose of their Comet containing the film reels with the recordings of the planes arriving at their destination. Their entire London-Melbourne-London journey had taken 13 days, 6 hours and 43 minutes: Cathcart-Jones and Waller were thus able to set a new world record.

G_ACSS "Grosvenor House" had won the race with a pure flight time of 71 hours; against the background of this performance, how had the dreaded US competition fared? The Dutch Douglas DC-3 with the registration and name PH-AJU Uiver took second place with 90 hours and 13 minutes, Boeing 247D followed closely behind in third place with 92 hours and 55 minutes.

This is Mikro Mir's 1:48 scale DH.88 Comet.

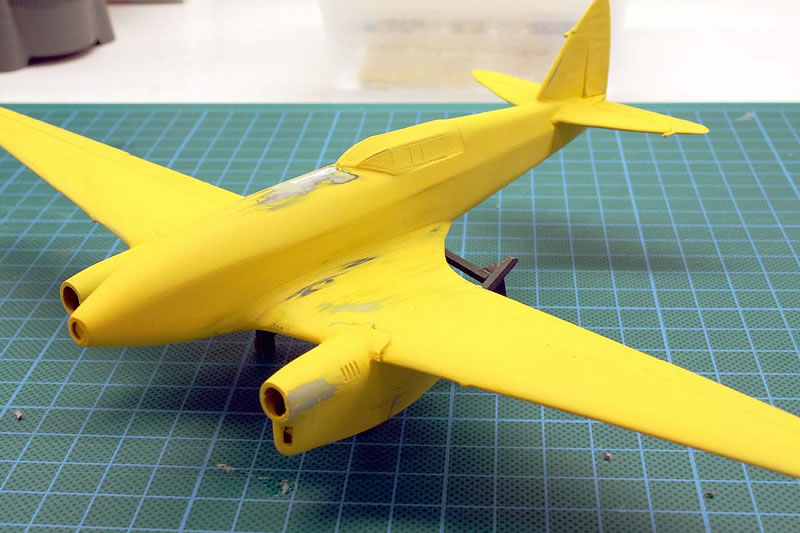

The DH.88 belongs to the group of kits that I started building as soon as they were ordered and delivered. The joy of being able to build a DH.88 Comet was too great to let the kit lie around for long!

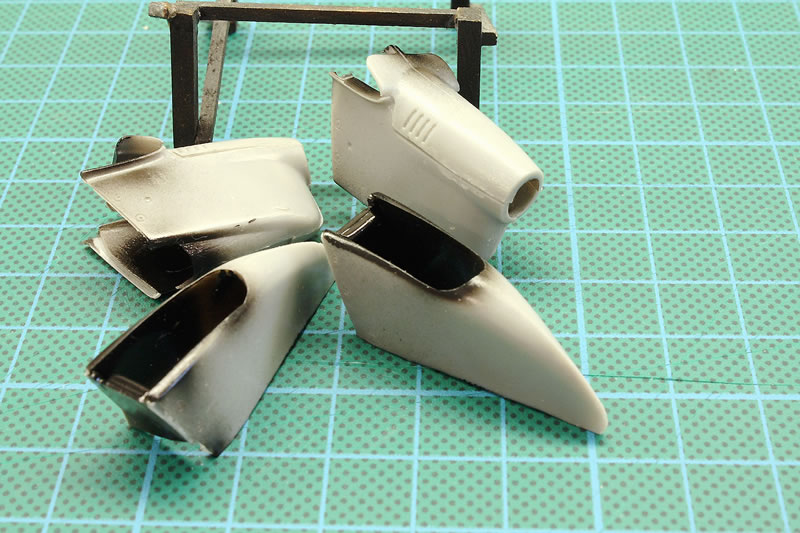

A first look into the bulging box also promised good things throughout, Mikro Mir seemed to have spared nothing here. I was particularly impressed by the engine representations, as both Gipsy Six could be shown here without fairings and in great detail.

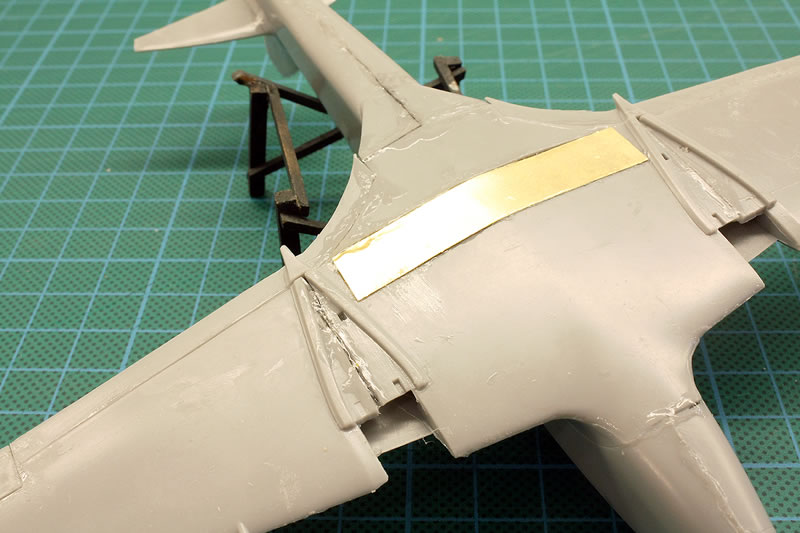

The construction itself is quite complex, if you really want to show the engines without covers, the construction steps have to be planned even more carefully. This also revealed a peculiarity of the parts: on the one hand, many details are magnificently prepared - but on the other hand, literally all parts have to be reworked, because fish-skin, sink marks and unclean castings are epidemic. As an example, I would like to point to the parts representing the cylinders of the Gipsy Six: really every single one has a small sink mark that would need to be filled. This peculiarity strengthened my decision to depict the Comet flying. I also liked this because it shows off the incredibly sleek shapes and elegant proportions of the DH.88 to best advantage.

As soon as the decision for a closed cockpit and a retracted landing gear was made, the kit could show its strengths: the shapes are splendidly hit and the construction proceeds largely fit. However, "largely" still means here: one should allow adequate time for filling and sanding in order to get close to the flowing and poorly textured surfaces of the Comet.

I am really grateful to Mikro Mir for finally giving the modelling world a coherent and well-buildable DH.88 Comet, nevertheless I guess the kit will rather make the ambitious and experienced modeller happy.

Finally, I would like to highly recommend Guy Inchbald's "The Comet Air Racers Uncovered" to all those interested in the DH.88. Most of the information given here can be found in it.

If you would like to see the kit and the building process for yourself, you can find a detailed building report on "Scalemates" here:

https://www.scalemates.com/profiles/mate.php?id=10148&p=albums&album=99886

As always, I am open to suggestions and questions:

ro.sachsenhofer@gmx.at

Model, Images and Text Copyright ©

2023 by Roland Sachsenhofer

Page Created 8 November, 2023

Last Updated

8 November, 2023

Back to HyperScale Main Page

|

Home

| What's New | Features | Gallery | Reviews | Reference | Resource Guides | Forum |